London's Future: More People, Fewer Cars

Mayor Sadiq Khan’s Draft London Plan sets out a vision of how Britain’s capital will change by 2029.

The London of 2029 will hold more people, have fewer cars, and boast better public transit. It should also be easier to find a place to lock your bike or get a pint of lager—and harder to hit up a fast-food joint after school. That, at least, is the vision set out in London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s new Draft London Plan, which sets out a vision of how Britain’s capital will change over the ten years following 2019.

A blockbuster of a document still subject to public consultation that Citylab will be returning to as it develops, the plan put together by the mayor’s office nonetheless has some clear themes running through it. London is going to build a lot more new housing, and those homes are overwhelmingly going to be in the outer boroughs. Most strikingly, those new residents may find it difficult to park their cars.

Clearing out the cars

The most eye-catching feature of the report is a near-blanket ban on new parking across much of the city. In Central London and in a constellation of new development zones grouped around outer transit hubs, new car parking spaces will be forbidden altogether. In the few, less central areas of inner London where new parking will be permitted, it will be at a rate of no more than 0.25 spaces per new housing unit.

This zero-tolerance policy may sound strict to future motorists, but it’s also part of a wholesale reimagining of London as a city where the automobile is an endangered species. (Already, private cars no longer dominate city streets.) There are major new transit links on the way, mentioned in the London Plan although not introduced by it. Beyond Crossrail 1— a major east-west heavy rail link due to start service next year—the plan predicts the approval of Crossrail 2, a new north-south counterpart that will ease access to central London from the suburbs and exurbs. Meanwhile, an extension of the existing Bakerloo tube line out to southeast London is also in the cards.

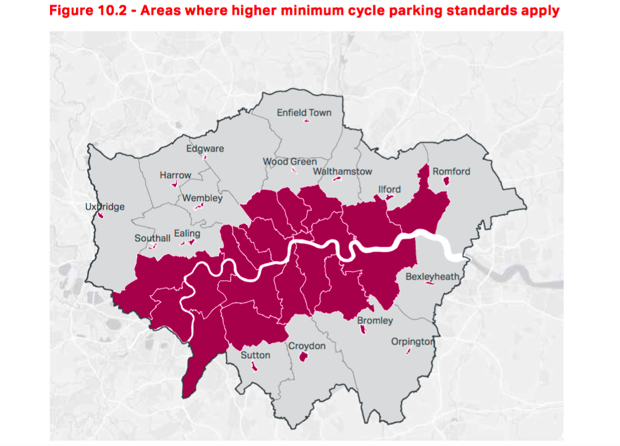

The only road-users who will get new parking are the ones riding bicycles: The plan calls for raised minimum bike space requirements for businesses and a new zone flanking most of the Thames’ banks where even higher minimums will be required for new construction.

A denser city, especially on the fringes

The parking ban is making a lot of headlines, but it’s actually the new housing targets outlined in the plan that will have the most transformative effects. London has a target of 650,000 new home completions for the 10 years following 2019. That’s like packing in a whole Manchester’s worth of housing stock.

Tellingly, when these targets are broken down, it’s the lower-density outer boroughs which have the more ambitious targets. That might seem obvious, but under Mayor Khan’s predecessor, current foreign secretary Boris Johnson, outer boroughs were often notorious for ducking their housing targets—and the then-mayor permitted this, leaving already relatively dense inner London to bear the brunt of development in ways that have often shattered low-income communities. In the new plan, however, the outer boroughs of Greenwich, Barnet, Croydon, Brent, and Ealing have by far the highest targets, placing local authorities under renewed pressure to find suitable land.

This won’t be easy: These areas aren’t exactly unbuilt. Indeed, by suburban American standards (and these areas are still called “the suburbs” by Londoners), they are hardly obvious in their abundance of buildable gaps.

The Draft London Plan shows awareness of this. In fact one of its key priorities is the development of smaller housing plots, of a scale that can house between one and 25 homes. The plan stipulates a target of 245,000 new homes on such sites, more than a third of all homes planned for the city. This seems prudent. Bar a few brownfield sites, there aren’t many large unused pockets in the outer boroughs, but there are many areas scattered with low-rise homes with large gardens that could be filled in with small homes, or parades of shops that could see upper floors added. Such efforts to cram in affordable units would be likely to meet some resistance, but the sheer value of space in London has already seen many homeowners adding as much extra space as they can within existing planning laws, extending kitchens and family rooms into their gardens, squaring out lofts into full rooms, and installing guest cabins or offices in gardens.

To push more rigorous thinking about such sites, the Mayor’s Office has created specific targets for small sites. Barnet and Croydon, both boroughs with many roomy, scattered neighborhoods, have been given the most to find space for. What the plan still rules out, however, is building on the Green Belt, the long-protected doughnut of open(ish) land that surrounds London and separates it from its satellite cities.

Yes to beer, no to fast food

Along with the major engineering of housing and parking targets, the plan also offers some lighter tinkering in order to make London more livable. Among the more eye-catching: a commitment to protecting pubs. The iconic British watering holes have been disappearing from London neighborhoods, as the city’s stressed housing market has made renting homes far more profitable than selling beer. A total of 1,220 pubs have closed in London since 2001 (a quarter of the city’s total), many of them converted to residences and sold to new owners, often at high prices, given the attractive Victorian and Edwardian London pub architecture that developers get to work with.

Losing them doesn’t just mean one less place to chat or get drunk—pubs typically have function rooms upstairs that host community meet-ups and special interest groups, provide space for private parties or, in keeping with common British habit, host post-funeral get-togethers.

Comments

Post a Comment