D.C.’s War Over Restaurant Tips Will Soon Go National

The District’s voters will decide Initiative 77, which would raise the minimum wage on tipped employees. Why don’t workers support it?

In less than a week, voters in Washington, D.C., will settle a national debate over tipping. The District’s upcoming primary election includes a ballot measure called Initiative 77, a policy to gradually raise the minimum wage that tipped workers receive. Two national restaurant groups are turning D.C. into a proxy war over a wide-reaching and politically fraught norm: the tip.

In one corner: One Fair Wage, the campaign to raise the base pay that waiters, bartenders, and other tipped workers earn in the District. The pro-77 side is almost entirely the work of Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC), a national nonprofit advocacy organization. If 77 passes, employers will pay a single minimum wage throughout the city. No more tiers. Currently, tipped-wage workers can make a lot more (or a lot less) than the regular minimum wage.

In the anti-77 corner: Save Our Tips, the campaign to preserve the status quo. A no vote means that tipped workers will continue to earn a sub-minimum base wage. Most local restaurant industry workers—owners and employees alike—have aligned themselves with the opponents of Initiative 77. But Save Our Tips is far from a grassroots push: Campaign finance records show that it’s principally a production of the National Restaurant Association, which bills itself as “the largest foodservice trade association in the world.”

So in some ways, Initiative 77 is a classic throw-down between labor and management, with a confusing twist: Across the city, bosses and workers are both fighting against the wage increase. Economists take a slightly different tack. Different parties have been squabbling over (and studying) the minimum wage since Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. But there’s a lot less information on the tipped wage as a phenomenon of its own.

While the empirical research on the tip-credit provision is threadbare, special-interest groups are nevertheless barreling ahead with this economic experiment. The nation should pay attention to what D.C. voters decide on June 19: After all, it’s national groups waging these restaurant wars, and they won’t stop here.

As a city with an electric restaurant scene and staggering racial disparities, D.C. is minding this vote closely. Arguments for and against Initiative 77 can be had all over town. Some of those points are more persuasive than others. Here’s a rundown of some of the questions, myths, inaccuracies, and scare tactics shaping this debate—and also a few bedrock truths.

“Initiative 77” is actually a plot from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

False! (You’re thinking of Section 31.) In fact, Initiative 77 is a ballot proposition to gradually raise base wages for tipped workers in D.C. over the course of eight years. Currently, these workers earn $3.33 per hour, plus tips. And currently, tipped workers are guaranteed the minimum wage ($12.50). That means that if tips don’t add up to at least $9.17 an hour, the employer pays the difference.

False! (You’re thinking of Section 31.) In fact, Initiative 77 is a ballot proposition to gradually raise base wages for tipped workers in D.C. over the course of eight years. Currently, these workers earn $3.33 per hour, plus tips. And currently, tipped workers are guaranteed the minimum wage ($12.50). That means that if tips don’t add up to at least $9.17 an hour, the employer pays the difference.

If Initiative 77 passes, the tipped minimum wage—that $3.33 basement rate—will increase, over eight gradual bumps, until it reaches whatever the minimum wage is in 2026. At that time, front-of-the-house staff at bars and restaurants—those are the servers, bartenders, hosts, sommeliers, and the like—will earn at least $15 an hour (which is what D.C.’s standard minimum wage will be in 2020).

Right now, employers and customers share the responsibility for paying tipped workers a minimum wage. If 77 passes, that duty would fall on employers alone.

If Initiative 77 passes, I don’t have to tip anymore!

No. Or there’s no reason to think so, based on the handful of states that have already banned the sub-minimum tipped wage.

No. Or there’s no reason to think so, based on the handful of states that have already banned the sub-minimum tipped wage.

“There has been absolutely no change in tipping practice, to the best of my knowledge, in any of the states that have no tipped minimum wages,” says David Cooper, senior economic analyst for the Economic Policy Institute, a think tank that favors 77. “Think about it: When folks cross the border from Arizona to California to go out to eat, do you think that they are aware of the difference in the state’s tipped wage policy and change their tipping behavior? I doubt it.”

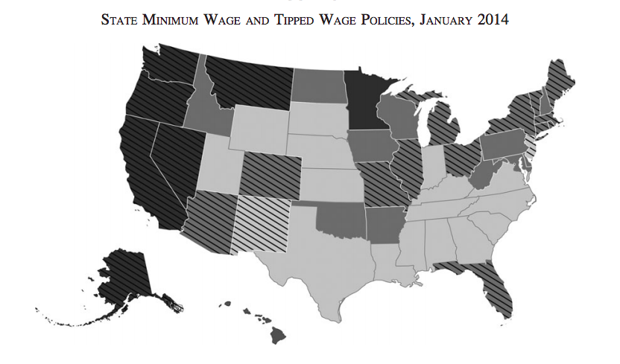

Light gray: States that use the federal tipped wage.

Medium gray: States that pay above the federal tipped wage.

Dark gray: States that do not have a tipped wage.

Hash marks: States whose standard minimum wage is higher than the federal minimum wage.

(Industrial Relations)

Since the District isn’t a state, it’s hard to compare it with places that prohibit the tipped wage, especially since some states (such as California) never used it in the first place. There’s only one real point of comparison: Flagstaff, Arizona. The state uses the federal tipped wage, but the city will start phasing it out in 2022, gradually increasing it to the city’s (higher) standard minimum wage in 2026.

I heard that tipped workers in D.C. already make a lot more than the minimum wage—$20, $30, or $40 an hour.

True and false. Front-of-the-house staff at most bars and restaurants in D.C. do make more than the minimum wage. Some make a lot more.

True and false. Front-of-the-house staff at most bars and restaurants in D.C. do make more than the minimum wage. Some make a lot more.

But tipped-wage employees also include people who don’t work in fancy restaurants, or in any restaurants. Valets, for example. Housecleaners and landscapers, too. Nail salon workers, an often invisible class of highly exploited immigrants, are also tipped-wage workers. Tipped workers are disproportionately women, people of color, and people living in poverty.

“I realize that when someone thinks of a tipped worker, they think of the waiter they had at Le Diplomate on Thursday night. But there’s a lot of other tipped workers in D.C.,” says Justin Zelikovitz, managing partner of D.C. Wage Law, a firm that specializes in wage-hour compliance. He says he’s argued four car-wash cases in the last year: While car-wash owners are obligated to pay their (mostly African-American and Latino) employees the difference between their cash wage and the minimum wage, plenty get away with paying far less.

“I don’t know if this is good policy or bad policy, but when you create an exception to the baseline rules, you create an opportunity for people to abuse those rules,” Zelikovitz says.

What if Initiative 77 raises costs so much that cocktails will go for $17.97 by 2026?

God, I hope so. Let me lock in my order now!

God, I hope so. Let me lock in my order now!

In an instant-classic media stunt, one D.C. speakeasy hosted a dystopian pop-up bar that imagined what prices would be like in a dark, gritty post-77 era. A gin rickey called “Came to the Wrong Town,” a drink that would normally set back drinkers $12, instead cost nearly $18—a demonstration of the severe consequences of a yes vote on 77. In reality, though, that price hike would be little more than the cost of an inflation increase over the last eight years. As a piece of agitprop, the 2026 pop-up bar flopped—especially since its operators gave one drink an egregiously racist name.

Comments

Post a Comment